Find the Fox with MCMC

Published:

$\newcommand{\N}{\mathbb{N}}$ $\newcommand{\R}{\mathbb{R}}$ $\newcommand{\E}{\mathbb{E}}$ $\newcommand{\C}{\mathbb{C}}$ $\renewcommand{\P}{\mathbb{P}}$ $\newcommand{\one}[1]{\boldsymbol{1}_{#1}}$

Since it was published in 2024, Alex Cheddar’s book Find the Fox: the Almost Impossible Word Search has become quite popular for its difficulty and novelty. If you haven’t heard of this book, the concept is very simple: it’s a word search where the grid consists solely of the letters F, O, and X. There’s only one word to find: FOX, which appears once among all 200 pages of the book. As is standard in word searches, the string can appear horizontally, vertically, or diagonally, and either forward or reversed. Here’s the first page of the book, extracted from the Amazon preview:

Upon a quick inspection, the letters seem to be fairly uniformly distributed – conditional, of course, on the string FOX not appearing (it’s definitely not on this page). This led me to think about how the book would have been generated (I certainly hope that Mr. Cheddar didn’t write the book1 manually, letter by letter!). Each of the 200 pages consists of a $32 \times 20$ grid. Assuming the letters really are randomly generated, the book can be said to have been sampled from the $\mathrm{Unif}(\{F,O,X\}^{32 \times 20 \times 200})$ distribution conditional on the string $FOX$ only appearing once. Sampling from this conditional distribution is not trivial. In this post, we’ll develop a method to do so using Python.

First of all, we can probably agree that any reasonable method will first sample from the distribution in which the string doesn’t appear anywhere, and then randomly choose a spot to insert it. The essential strategy behind the last part is fairly straightforward: we simply overwrite some $3$-letter string to $FOX$, and then ensure that we haven’t inadvertently created additional $FOX$s in the process. So for now, let’s focus on generating a single $FOX$-less grid. Call a grid valid if it doesn’t contain the string $FOX$ anywhere, and let $\Omega$ be the set of valid $32 \times 20$ grids. We want to sample from the $\text{Unif}(\Omega)$ distribution, which we’ll call $\pi$ (as per tradition).

Exact Sampling

In principle, the simplest way to sample from $\pi$ is by rejection sampling: that is, we keep sampling from $\mathrm{Unif}(\{F,O,X\}^{32 \times 20})$ distribution until we produce a grid in $\Omega$. The only challenge here is coding up a valid grid checker, which is more of a programming exercise than anything else. Here’s a way to do it:

import random

letters = ("F", "O", "X")

height, width = 32, 20

# 8 directions (dx, dy)

dirs = [(0,1), (1,0), (1,1), (1,-1),

(-1,0), (0,-1), (-1,1), (-1,-1)]

def in_bounds(r, c):

return 0 <= r < height and 0 <= c < width

def violates_local(grid, r, c, directions):

# check whether FOX appears in any 3-cell segment that includes (r,c), along any direction

for dr, dc in directions:

# the triple can be (r-2dr,r-dr,r), (r-dr,r,r+dr), or (r,r+dr,r+2dr)

for offset in (-2, -1, 0):

coords = [(r + (offset + k)*dr, c + (offset + k)*dc) for k in range(3)]

if all(in_bounds(rr, cc) for rr, cc in coords):

triple = tuple(grid[rr][cc] for rr, cc in coords)

if triple in (letters, letters[::-1]):

return True

return False

def is_valid(grid):

# full scan

for r in range(height):

for c in range(width):

if violates_local(grid, r, c, dirs):

return False

return True

The rejection sampler then follows:

random.seed(1729)

validgrid = False

while not validgrid:

newgrid = [[random.choice(letters) for _ in range(width)] for _ in range(height)]

validgrid = is_valid(newgrid)

print(newgrid)

Because the proposal distribution is uniform over all $3^{32 \cdot 20}$ grids, the accepted sample is exactly uniform over the valid ones. So in theory, this works! You can try running this if you want, but I wouldn’t recommend it. Why? The problem is the acceptance rate $p_\text{acc}$. Computing the exact acceptance rate is essentially an inclusion-exclusion/transfer-matrix counting problem which explodes combinatorially in $2$ dimensions, but we can compute a rigorous upper bound.

Let $N$ be the number of length-$3$ segments we’re checking. Checking for a valid grid is equivalent to checking the four “forward” directions (→, ↓, ↘, ↙) — of which there are

\[20(32 - 2) + (20-2)32 + 2(32-2)(20-2) = 2256 \notag\]segments — for the presence of the strings $FOX$ and $XOF$. For each segment, we’re forbidding $2$ out of $3^3$ patterns, so the probability that a single segment is invalid is $2/27$. The expected number of invalid segments in a random grid is then $2256 \cdot (2/27) = 167.111\ldots$. For a quick upper bound on the acceptance probability, we can consider only disjoint segments. In each row of length $20$ we can choose $6$ disjoint horizontal triples (covering $18$ cells), which across $32$ rows comes to $192$ independent triples. If the grid is valid, then none of these triples can be $FOX$ and $XOF$, and hence

\[p_\text{acc} \leq \left(1 - \frac{2}{127}\right)^{192} \approx 3.83 \times 10^{-7}.\notag\]So the acceptance rate is at most about one in 2.6 million, which doesn’t seem horrible if we’re running our code on a peppy, multithreaded processor and we’re willing to wait for a few days. In fact, this bound is misleadingly optimistic — it overstates the probability by a factor of over 300 octillion.

To show this, we can invoke Janson’s inequality,2 which provides exponential upper bounds on the probability that none of a large collection of weakly dependent “bad” events occur, in terms of their expected count and the sum of their pairwise dependencies. Let $A_i$ be the event that segment $i$ is $FOX$ or $XOF$. Then the events $A_i$ and $A_j$ are independent unless the segements $i$ and $j$ share at least one cell. Define

\[X := \sum_{i=1}^m \mathbf{1}_{A_i}, \qquad \mu := \E[X] = \sum_{i=1}^m \P(A_i), \qquad \text{and} \qquad \Delta := \sum_{\substack{1 \leq i < j \leq m\\ i \sim j}} \P(A_j \cap A_j),\notag\]where $i \sim j$ means that segments $i$ and $j$ overlap and $m$ is the number of overlapping pairs of segments. The probability that we want is $p_\text{acc} = \P(X = 0)$, which, according to Janson’s inequality,3 is bounded above by $\exp(-\mu + \Delta/2)$. How can we compute $\mu$ and $\Delta$? Observe that $\mu$ is simply the expected number of invalid segments in the random grid, which we computed above as $167.111\ldots$. To compute $\Delta$, note that for each pair $(i,j)$, there are $4$ pattern combinations:

\[C := \{(FOX, FOX), (FOX, XOF), (XOF, FOX), (XOF, XOF)\}.\notag\]For each combination, we have a set of letter constraints on the union of the cells used by the two segments. Because the letters are independent and uniform, if the constraints are inconsistent (i.e., the same cell is required to be both $F$ and $X$), then $\P(A_i \cap A_j) = 0$; otherwise, the union involves $m_{ij} \in \{4,5\}$ distinct cells and

\[\mathbb{P}(A_i \cap A_j) = \sum_{c \in C} \mathbf{1}_{\{ \text{combination } c \text{ is consistent for } (i,j) \}}\, \cdot 3^{-m_{ij}}. \notag\]We thus compute:

from collections import defaultdict

from itertools import combinations, product

# generate all length-3 segments

segments = [

tuple((r + k*dr, c + k*dc) for k in range(3))

for r in range(height) for c in range(width)

for dr, dc in dirs[:4]

if all(in_bounds(r + k*dr, c + k*dc) for k in range(3))

]

# index segments by cell

cell_to_segs = defaultdict(list)

for i, seg in enumerate(segments):

for cell in seg:

cell_to_segs[cell].append(i)

# get all overlapping segment pairs

pairs = {

tuple(sorted(p))

for idxs in cell_to_segs.values()

for p in combinations(idxs, 2)

}

# compute probability that two segments are both FOX/XOF

def pair_prob(s1, s2):

total = 0.0

for p1, p2 in product((letters, letters[::-1]), repeat=2):

req = {}

ok = True

for (cell, ch) in zip(s1, p1):

if cell in req and req[cell] != ch:

ok = False; break

req[cell] = ch

for (cell, ch) in zip(s2, p2):

if cell in req and req[cell] != ch:

ok = False; break

req[cell] = ch

if ok:

total += 3 ** (-len(req))

return total

Delta = sum(pair_prob(segments[i], segments[j]) for i, j in pairs)

print(Delta)

This gives $\Delta \approx 171.4567$. Hence $p_\text{acc} \leq e^{-81.3827} \approx 1.2 \times 10^{-36}$. Conclusion: don’t use the rejection sampler.

There’s another way to sample exactly from our target distribution, this time using a bit of dynamic programming. To start off, define a scanning order (say row-by-row). At each step, to choose the next letter uniformly, we count how many completions exist if we put $F$ here, how many exist if we put $O$, and how many exist if we put $X$. Then we sample from the three letters with probabilities proportional to those completion counts. Seems simple enough! The catch is that for length-$3$ strings in $8$ directions, whether a choice is valid depends on a “neighborhood” of “radius” $2$, and the state we need to remember while sweeping is essentially the previous two rows (across their full widths), plus the last two letters of the current row we’re moving across. The number of states is on the order of $3^{2w}$, where $w$ is the width of the grid. For $w = 20$, it’s hopeless.4

Approximate Sampling

Instead of trying to sample from $\pi$ directly, what if we start off with some valid grid, and then modify it so that it looks like it came from $\pi$? This is where we can exploit MCMC. We will define a symmetric random walk on $\Omega$, where each step makes a tiny local random change but does not violate the constraint. Generating a valid grid (call it $G_0 \in \Omega$) is easy for initialization purposes: for example, the grid consisting entirely of $F$s is perfectly valid. Let’s now construct our Markov chain. At the $t$th iteration of our sampler, we’ll do the following:

- Choose a cell $(i,j)$ in $G_t$ uniformly at random

- Propose changing the letter in that cell to one of the other two letters (chosen uniformly)

- If the resulting grid is still valid (i.e., we didn’t create a new $FOX$), then accept the move and call the new grid $G_{t+1}$; otherwise, reject the proposed change and set $G_{t+1} = G_t$

The resulting chain $\{G_t\}_t$ is obviously time-homogenous. But is $\pi$ really stationary for this Markov chain? Let $G, G’ \in \Omega$ differ in exactly one cell (say the $k$th), and suppose that changing the cell from letter $a$ to letter $b$ keeps the grid valid. The probability of moving from $G$ to $G’$ is

\[\begin{align*} \P(G \to G') &= \P(\mbox{we pick cell $k$}) \cdot \P(\mbox{we propose letter $b$}) \cdot \P(G' \in \Omega)\\ &=\frac{1}{32 \cdot 20} \cdot \frac{1}{2} \cdot 1\\ &=\frac{1}{1280} \end{align*}\]and the probability of the reverse move is exactly the same. Since $\pi(G) = 1/\lvert\Omega\rvert$ for any $G \in \Omega$, we have

\[\pi(G) \cdot \P(G \to G') = \pi(G') \cdot \P(G' \to G).\notag\]So the detailed balance condition is satisfied, and $\pi$ is indeed stationary for our Markov chain.

What about aperiodicity? If we form a graph $\mathcal{G}$ whose vertices are grids in $\Omega$ and draw an edge between vertices $G$ and $G’$ if and only if the grids differ in exactly one cell, then we can view our algorithm as a random walk on $\mathcal{G}$. A random walk on an undirected graph is aperiodic if and only if the graph is non-bipartite, and for $\mathcal{G}$ to be non-bipartite, it suffices to find an odd cycle. But that’s easy! Start from the all-$F$ grid, then change the first cell to an $O$, then to an $X$, and then to an $F$. All of these grids are clearly in $\mathcal{G}$, so we’ve exhibited a cycle of length $3$ (i.e., a triangle), and our Markov chain is aperiodic.

The only tricky bit is irreducibility. In order to guarantee that the law of $G_t$ will actually converge to $\pi$ as $t \to \infty$, we need to show that our chain is irreducible: any valid grid should be reachable from any other via valid single-cell flips. Equivalently, we need to show that $\mathcal{G}$ is connected. Fortunately, with some care we can prove this. To be general, we’ll prove the result for any grid size.

For some setup, fix integers $h,w \geq 1$ and identify grid cells with coordinates $(r,c)$ where $r \in \{1,\ldots,h\}$ and $c \in \{1,\ldots,w\}$. A length-$3$ line segment is any triple of distinct cells of the form

\[(r,c), (r + \delta_r, c + \delta_c), (r + 2\delta_r, c + 2 \delta_c)\notag\]where

\[(\delta_r, \delta_c) \in \{(-1,0), (1,0), (0,-1), (0,1), (-1,-1), (-1,1), (1,-1), (1,1)\}\notag\]and all three cells lie in the grid. Define a valid single-cell flip to be an operation that changes the letter in exactly one cell and results in another grid in $\Omega$. We order the cells in row-major order: $(r,c) \prec (r’,c’)$ if either $r < r’$ or $r = r’$ and $c < c’$. Let $C_1, C_2, \ldots, C_{hw}$ denote the cells in this order. $G(C_i)$ refers to the letter in the $i$th cell of $G$.

Proposition: For every $G \in \Omega$, there exists a sequence of valid single-cell flips that transforms $G$ into the all-$O$ grid. Consequently, $\mathcal{G}$ is connected.

Proof: We will explicitly construct a valid path from an arbitrary $G \in \Omega$ to the all-$O$ grid. We process cells in row-major order. For $i = 1, 2,\ldots, hw$, at step $i$ we change the value of cell $C_i$ to $O$ if it’s not already $O$. Fix $i$ and let $G^{(i)}$ denote the grid after step $i$, with $G^{(0)} := G$. It is immediate that $G^{(i)}(C_j) = O$ for all $j \leq i$ (i.e., this is an invariant). We will show by induction that $G^{(i)} \in \Omega$. We already know that $G^{(0)} \in \Omega$, so suppose that $G^{(i-1)} \in \Omega$ and consider the transition $G^{(i-1)} \to G^{(i)}$, where we set $C_i$ to $O$. Any newly created forbidden pattern $FOX$ or $XOF$ would need to involve $C_i$, since all other cells are unchanged. Moreover, $O$ must appear in the middle of such a triple. Therefore, if setting $C_i$ to $O$ creates a forbidden pattern, then $C_i$ must be the center cell of some length-$3$ line segment whose two opposite neighbors have labels $F$ and $X$ in $G^{(i)}$.

It thus suffices to show that after the update, $C_i$ cannot have opposite neighbors $F$ and $X$ along any of the four lines through $C_i$ (horizontal, vertical, and the two diagonals). Let $C_i = (r_i, c_i)$. Consider any pair of opposite neighbors of $C_i$ along a line segment of length $3$ (when such neighbors exist within the grid). These opposite pairs are:

- Horizontal: $(r_i, c_i-1)$ and $(r_i, c_i+1)$

- Vertical: $(r_i-1, c_i)$ and $(r_i+1, c_i)$

- Diagonal NW-SE: $(r_i-1, c_i-1)$ and $(r_i+1, c_i+1)$

- Diagonal NE-SW: $(r_i-1, c_i+1)$ and $(r_i+1, c_i-1)$

In every case, one of these two neighbors either lies in a strictly earlier row than $C_i$, or in the same row but an earlier column. Concretely:

- In the horizontal pair, $(r_i, c_i-1) \prec (r_i,c_i)$

- In the vertical pair, $(r_i-1, c_i) \prec (r_i,c_i)$

- In the diagonal NW-SE pair, $(r_i-1, c_i-1) \prec (r_i,c_i)$

- In the diagonal NE-SW pair, $(r_i-1, c_i+1) \prec (r_i,c_i)$

Thus, whenever a length-$3$ segment centered at $C_i$ exists, at least one of the two opposite neighbors is some $C_j$ with $j < i$. By the induction invariant applied at step $i-1$, that neighbor is already $O$ in $G^{(i-1)}$, and it remains $O$ in $G^{(i)}$ since we only changed $C_i$. Therefore, in $G^{(i)}$ every existing opposite-neighbor pair around $C_i$ contains at least one $O$. In particular, it is impossible for the two opposite neighbors to be $F$ and $X$ (in some order). Hence no forbidden pattern can be centered at $C_i$, and so setting $C_i$ to $O$ cannot create a forbidden pattern. We conclude that the move $G^{(i-1)} \to G^{(i)}$ is valid; that is, $G^{(i)} \in \Omega$. This completes the induction step. After $hw$ steps, every cell has been set to $O$, so $G^{(hw)}$ is the all-$O$ grid. This proves that every $G \in \Omega$ can be transformed to the all-$O$ grid through a sequence of valid single-cell flips.

Now, take any two grids $G, G’ \in \Omega$. By the previous construction, there exists a valid path from $G$ to the all-$O$ grid, and likewise from $G’$ to the all-$O$ grid. Reversing the second path gives a valid path from the all-$O$ grid to $G’$, and concatenating the first path and the reversed second path yields a valid path from $G$ to $G’$. Thus $\mathcal{G}$ is connected. $\square$

So our Markov chain is irreducible and aperiodic, and therefore has a unique stationary distribution. Since $\pi$ is stationary (as we verified from the detailed balance condition), it is the unique stationary distribution, and for any starting state $G_0 \in \Omega$, we have $\mathcal{L}(G_t) \to \pi$ as $t \to \infty$ by the standard finite-state Markov chain convergence theorem.

It remains to actually code up our sampler. We’ll go for $1{\small,}100{\small,}000$ iterations, burn off the first $50{\small,}000$ and thin every $50{\small,}000$th sample. These numbers may seem large compared to what you’d often see in simpler applications (especially in continuous-space settings), but remember that our Markov chain transitions are local moves in an enormous, heavily constrained state space, so mixing is necessarily slow: changing the large-scale features of a grid requires a lot of accepted local moves, so we’ll need a lot of iterations before the chain forgets its initialization and reaches more typical configurations. We thin aggressively because successive states of the chain are highly correlated; each iteration proposes a change at a single cell, so even accepted moves alter only one of $32 \times 20 = 640$ cells. As a result, many iterations are required before the chain produces a meaningfully different grid, and large thinning factor gives us approximately independent-looking samples; similarly, a large burn-in period allows us to confidently move past the all-$F$ initialization grid.

def step(grid, lazy_p=0.5):

r = random.randrange(height)

c = random.randrange(width)

old = grid[r][c]

new = random.choice([x for x in letters if x != old])

grid[r][c] = new

if violates_local(grid, r, c, dirs[:4]): # reject if we created a forbidden triple

grid[r][c] = old

def run_chain(steps=1_100_000, burn=50_000, thin=50_000, seed=None):

if seed is not None:

random.seed(seed)

# start from an easy valid state (all F)

grid = [["F"] * width for _ in range(height)]

snapshots = []

for t in range(1, steps + 1):

step(grid)

if t >= burn and (t - burn) % thin == 0:

snapshots.append(["".join(row) for row in grid])

return snapshots

pages = run_chain(seed=1729)

print("\n".join(pages[0][:10]))

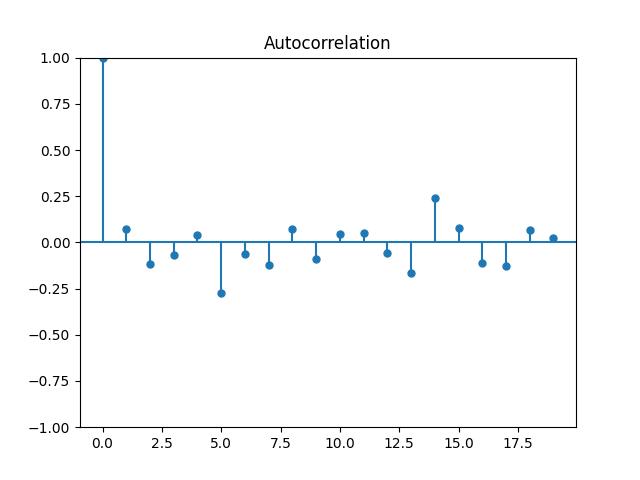

This takes about 10 seconds to run and produces 20 grids. Some quick MCMC diagnostics: our acceptance rate is a healthy $0.452$, and the frequencies of the letters $F$, $O$, and $X$ at the last sampled grid are $0.323$, $0.328$, and $0.348$ respectively, which is about what we’d expect. More precisely, each of those is the observed value of the pushforward of $\pi$ under the coordinate projection onto a single cell, taking values in $\{F,O,X\}$. The unconditional distribution $\text{Unif}(\{F,O,X\}^{32 \times 20})$ is invariant under any permutation of the letters, and the conditioning event “no FOX appears” that defines $\pi$ is also invariant under relabelling the letters. Thus $\pi$ is exchangeable in the letters, and it follows by symmetry that $\pi$ assigns mass $1/3$ to each letter (so the “local” letter frequencies remain uniform despite rather strong global conditioning). An acf plot suggests that the autocorrelation of the resulting samples decays reasonably fast:

Now, finally, what about putting in a $FOX$? To do this, we can simply sample one of our grids (uniformly at random) and then change a $3$-letter segment to $FOX$.5 The harder part is ensuring that this doesn’t accidentally create another $FOX$ nearby via overlapping triples. To do this, we’ll construct a function that picks a random $3$-letter segment uniformly from the grid, and then overwrites it with either $FOX$ or $XOF$ (with equal probability). Now, observe that if an arbitrary $3$-letter segment in the grid doesn’t touch any changed cell, then its three letters are exactly the same as before, so it couldn’t suddenly become $FOX$ if it wasn’t already. Thus, if there are other $FOX$s after the overwrite, we know that they must be among the length-$3$ segments that intersect the cells that we changed. So we need only enumerate those segments, of which there are a constant number. If, among those segments, we count more than one $FOX$, we undo the overwrite and try again with another random segment.

segments = []

for r in range(height):

for c in range(width):

for dr, dc in dirs[:4]: # →, ↓, ↘, ↙

coords = [(r + k*dr, c + k*dc) for k in range(3)]

if all(in_bounds(rr, cc) for rr, cc in coords):

segments.append((tuple(coords), (dr, dc)))

def segments_through_cell(r, c):

# all length-3 segments (4 directions) that include (r,c)

out = []

for dr, dc in dirs[:4]:

for off in (-2, -1, 0):

coords = [(r + (off+k)*dr, c + (off+k)*dc) for k in range(3)]

if all(in_bounds(rr, cc) for rr, cc in coords):

out.append(tuple(coords))

return out

def count_fox_in_affected(grid, affected_cells):

# count FOX/XOF occurrences among segments that intersect affected_cells

seen = set()

total = 0

for (r, c) in affected_cells:

for seg in segments_through_cell(r, c):

if seg in seen:

continue

seen.add(seg)

triple = tuple(grid[rr][cc] for rr, cc in seg)

if triple in (letters, letters[::-1]):

total += 1

return total

def inject_exactly_one_fox(grid, max_tries=200000):

for _ in range(max_tries):

(cells, (dr, dc)) = random.choice(segments)

pat = random.choice((letters, letters[::-1])) # choose FOX or XOF orientation on this segment

new = [row[:] for row in grid]

changed = []

for (rr, cc), ch in zip(cells, pat):

if new[rr][cc] != ch:

new[rr][cc] = ch

changed.append((rr, cc))

# if we didn't change anything, we'd still have 0 occurrences — skip

if not changed:

continue

# starting grid has 0; any new occurrence must touch a changed cell

if count_fox_in_affected(new, changed) == 1:

return new, {"cells": cells, "dir": (dr, dc), "pattern": pat}

raise RuntimeError("Failed to inject exactly one FOX; increase max_tries.")

Somewhat counterintuitively, most random overwrites of $FOX$ won’t actually create extra $FOX$s, because to do so requires a fairly specific local coincidence: the overwritten letters must also complete another length-$3$ pattern passing through one of the modified cells. Since we only alter $3$ cells, the “impact radius” is small, so the probability of collateral $FOX$s is small as well. You can try this with the first page of Find the Fox above: try to pick any length-$3$ segment at random,6 change the letters to $FOX$, and see if that change created any extra $FOX$s. Chances are that it didn’t!

Finally, we can create a fresh “book” with as many pages as we’d like. For example, you might like the idea of Find the Fox but think that 200 pages is a bit much. We can easily create a single page with exactly one $FOX$ in it! And once we solve that one, we can create another one (and continue ad nauseam until we get bored of finding foxes, which I imagine won’t take very long). Here’s some code to generate a reasonably pretty PDF:

from reportlab.pdfgen import canvas

from reportlab.lib.pagesizes import letter as LETTER

from reportlab.lib.colors import black, red

def write_grids_pdf(filename, grids, fox_marks=None):

c = canvas.Canvas(filename, pagesize=LETTER)

page_w, page_h = LETTER

# page layout stuff

margin_x = 72

margin_top = 60

margin_bot = 60

# grid area bounds

grid_top = page_h - margin_top - 40

grid_bot = margin_bot + 30

avail_h = grid_top - grid_bot

avail_w = page_w - 2 * margin_x

for i, rows in enumerate(grids):

# build lookup for highlighted cells on this page

red_cells = set()

if fox_marks is not None and fox_marks[i] is not None:

red_cells = set(fox_marks[i].get("cells", []))

n_rows = len(rows)

n_cols = len(rows[0]) if n_rows else 0

fs_h = avail_h / (n_rows * 1.35)

fs_w = avail_w / (n_cols * 1.30)

font_size = min(fs_h, fs_w) * 1.15

font_size = max(8, min(18, font_size))

c.setFont("Times-Roman", font_size)

char_w = c.stringWidth("M", "Times-Roman", font_size)

tracking = char_w * 0.70 # spacing between letters

pitch = char_w + tracking

line_h = font_size * 1.25

grid_w = pitch * (n_cols - 1) + char_w

grid_h = line_h * (n_rows - 1) + font_size

start_x = (page_w - grid_w) / 2

start_y = grid_bot + (avail_h + grid_h) / 2 # near top of grid area

# draw grid

y = start_y

for r, row in enumerate(rows):

x = start_x

for cc, ch in enumerate(row):

c.setFillColor(red if (r, cc) in red_cells else black)

c.drawString(x, y, ch)

x += pitch

y -= line_h

# page number (bottom center)

c.setFillColor(black)

c.setFont("Times-Roman", 10)

c.drawCentredString(page_w / 2, margin_bot / 2, str(i + 1))

c.showPage()

c.save()

def make_book(n_pages=1,

steps=1_100_000,

burn=50_000,

thin=50_000,

seed=1729,

out_pdf="find_the_fox.pdf",

out_key_pdf="find_the_fox_answer_key.pdf"):

random.seed(seed)

pages = run_chain(steps=steps, burn=burn, thin=thin, seed=seed)

if len(pages) < n_pages:

raise ValueError(f"run_chain produced only {len(pages)} snapshots; need {n_pages}. "

"Increase number of steps or reduce thinning factor.")

pages = pages[:n_pages]

# choose which page gets the FOX/XOF

j = random.randrange(n_pages)

# inject exactly one FOX/XOF on that page

grid = [list(row) for row in pages[j]]

new_grid, info = inject_exactly_one_fox(grid)

pages_with_fox = list(pages)

pages_with_fox[j] = ["".join(row) for row in new_grid]

# book PDF: no highlighting

write_grids_pdf(out_pdf, pages_with_fox, fox_marks=[None]*n_pages)

# answer key PDF

marks = [None]*n_pages

marks[j] = info

write_grids_pdf(out_key_pdf, pages_with_fox, fox_marks=marks)

return {"fox_page_index": j, "fox_info": info}

result = make_book(n_pages=1)

print("The FOX is on page", result["fox_page_index"] + 1)

print("FOX info:", result["fox_info"])

Here’s the generated page, and here’s the solution key with the $FOX$ coloured in red. Enjoy! If you liked this, please support the author and publisher of Find the Fox and purchase the book! Once you’ve solved it, come back here and generate an iid copy of the book and start again.

Or rather, books. The answer page for the book asks you to input the serial number, which suggests that different printings of the book have different solutions. ↩

Not a typo: Jensen’s inequality is completely different. ↩

See Theorem 8.1.2 of these course notes by Yufei Zhao, for example. ↩

On the other hand, if you were okay with very narrow or very short grids — say $5$-ish characters wide or high — then this would work pretty nicely, since the running time is linear in the dimension you’re not scanning over. ↩

Your first thought might instead be to randomly choose a length-$3$ segment that’s one letter away from $FOX$ (i.e., of the form $\ast OX$, $F\!\ast\!X$, or $FO\ast$ where the wildcard letter doesn’t complete a $FOX$) and simply insert the missing letter. This one-cell change has a smaller “impact radius”, and the conditional acceptance probability will tend to be higher. However, there are two drawbacks to this approach. First, we’d have to scan the grid looking for such near-misses and then choose one at random, which is much more expensive than just choosing an arbitrary length-$3$ segment. Second (and more importantly), this method won’t actually place the $FOX$ uniformly among all possible segments. Because we only consider segments that already partially resemble $FOX$, the probability that a given location and orientation is chosen depends on local letter statistics, which ends up biasing our sampler. ↩

This is important: if you specifically look for a length-$3$ segment that has two of the three $FOX$ letters in the correct positions (e.g., $FFX$, $XOX$, etc.) and it’s not on the boundary of the grid, then you can guarantee at least two $FOX$s with a carefully chosen overwrite. ↩